The United Nations (UN) General Assembly has proclaimed June 19 of each year to be the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict in order to raise awareness of the need to put an end to conflict-related sexual violence and to honor the victims and the survivors of sexual violence around the world. The date was chosen to commemorate the adoption on June 19, 2008 of Security Council Resolution 1820 in which the Council condemned sexual violence as a tactic of war and as an impediment to peacebuilding.

For the UN, “conflict-related sexual violence” refers to rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced abortion, and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls, and boys, linked to a conflict. The term also encompasses trafficking in persons when committed in situations of conflict for purposes of sexual violence or exploitation.

There has been a slow growth of awareness-building trying to push UN Agencies to provide non-discriminatory and comprehensive health services including sexual and reproductive health services taking into account the special needs of persons with disabilities. A big step forward was the creation of the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. The post is currently held since April 2017 by Under-Secretary-General Pramila Patten. She recently said “We see it too often in all corners of the globe from Ukraine to Tigray in northern Ethiopia to Syria and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Every new wave of warfare brings with it a rising tide of human tragedy including new waves of war’s oldest, most silenced and least-condemned crime.”

The Association of World Citizens (AWC) first raised the issue in the UN Commission on Human Rights in March 2001 citing the judgement of the International Court for Former Yugoslavia which maintained that there can be no time limitations on bringing the accused to trial. The tribunal also reinforced the possibility of universal jurisdiction that a person can be tried not only by his national court but by any court claiming universal jurisdiction and where the accused is present.

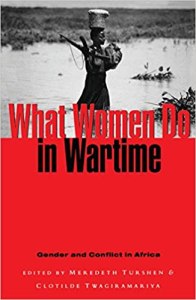

The AWC again stressed the use of rape as a weapon of war in the Special Session of the Commission on Human Rights on the Democratic Republic of Congo, citing the findings of Meredeth Turslen and Clotilde Twagiramariya in their book What Women Do in Wartime: Gender and Conflict in Africa (London: Zed Press, 1998), “There are numerous types of rape. Rape is committed to boast the soldiers’ morale, to feed soldiers’ hatred of the enemy, their sense of superiority, and to keep them fighting: rape is one kind of war booty; women are raped because war intensifies men’s sense of entitlement, superiority, avidity, and social license to rape: rape is a weapon of war used to spread political terror; rape can destabilize a society and break its resistance; rape is a form of torture; gang rapes in public terrorize and silence women because they keep the civilian population functioning and are essential to its social and physical continuity; rape is used in ethnic cleansing; it is designed to drive women from their homes or destroy their possibility of reproduction within or “for” their community; genocidal rape treats women as “reproductive vessels”; to make them bear babies of the rapists’ nationality, ethnicity, race or religion, and genocidal rape aggravates women’s terror and future stigma, producing a class of outcast mothers and children – this is rape committed with consciousness of how unacceptable a raped woman is to the patriarchal community and to herself. This list combines individual and group motives with obedience to military command; in doing so, it gives a political context to violence against women, and it is this political context that needs to be incorporated in the social response to rape.”

The prohibition of sexual violence in times of conflict is now part of international humanitarian law. However, there are two major weaknesses in the effectiveness of international humanitarian law. The first is that many people do not know that it exists and that they are bound by its norms. Thus, there is a role for greater promotional activities through education and training to create a climate conducive to the observance of internationally recognized norms. The second weakness is enforcement. We are still at the awareness-building stage. Strong awareness-building is needed.

************************************

Rene Wadlow, President, Association of World Citizens